Creating Art from Alienation

For as long as she can remember, Lauren Burke has felt observed by what she calls “outsider eyes.” The eyes scrutinized her multiracial family whenever they were in public, scanning their faces to try to understand “what” they were.

My mother’s family is from South Korea and my father’s family is originally Irish,” says Burke. “People actually have come up to my brother, my parents, and me and told us which kid looks more like my mother or my father — they don’t make any secret that they’re observing us.”

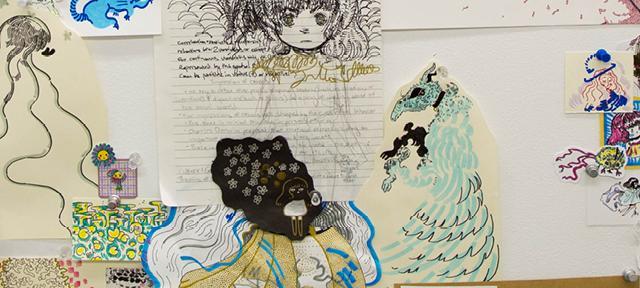

For her Div III, Burke decided to explore her identity through art — specifically, the medium of the tunnel book.

A type of book art akin to pop-ups, tunnel books create three-dimensional scenes — almost like small stage sets — that pair words and images. People look into the scenes through an aperture cut into the cover, creating a “tunnel” into the scene. The books are intricately crafted by cutting and layering pieces of paper.

Burke first learned about tunnel books in a class with Andrea Dezsö, a professor of art at Hampshire, who works across a broad range of media, including cut paper.

Burke’s project is an installation of nine interrelated tunnel books, each focusing on a specific theme based on, she says, “moments, spaces, and people that I’ve experienced as a white-passing multiracial person who strongly connects with Asian American culture and identity.”

Themes range from the highly personal (her relationship with her brother, her parents’ multicultural marriage), to the political (depictions of the demilitarized zone separating South Korea and North Korea), to cultural touchstones, such as food.

Among Burke’s visual referents are graphic novels and classical Korean art. She recalls that during middle school, she began tuning into Korean TV shows, music, and other facets of pop culture and found them to be “a great starting point to connect to my Korean heritage with a new level of awareness,” she says. “These memories I’m hoping to convey in the tunnel books are a mix of deep pride in my family and our culture as well as moments of pain through micro-aggressions and blatant acts of racism I’ve witnessed and experienced myself."

One of her tunnel books, for example, depicts her family sitting together in the center of a hearth-like circle — but they’re surrounded by a ring of prying eyes.

A native of Los Angeles, Burke spent her early childhood through middle school years in what she calls a “bubble environment of mixed families where being interracial was normalized.” Then came a move to a large high school. There, she first experienced her surroundings as a hostile space, where “people were policing what I was doing while I was doing it.”

Burke recalls feeling as if she were “a puzzle the other students were trying to solve. People would come up to me and say, ‘I knew you weren’t just white.’ But I’m not a puzzle. I’m a person. Those kinds of comments created a dissociation with my body for me.”

Equally invasive, she says, are the “loaded” topics people bring up in casual conversation.

“They’ll ask if I’m North Korean or South Korean,” Burke explains. “These are interactions that can happen very quickly after you meet someone. I don’t necessarily want to tell them right then that the reason we have a North Korea and a South Korea is because the United States is directly responsible for this situation. Other people’s struggles to understand my family’s personal history — or not — don’t need to be small talk at a dinner party. It’s not casual conversation.”

Within her art — and in each of the tunnel books—Burke has created a safe space to process her life as a multiracial person.

“The goal for this project is to share my experiences with a wider audience who are unfamiliar with the struggles of being multiracial, so they can begin to understand the expectations they often push on members of this community,” she says.