Div III Profile: Humphrey-Blanco Studies Genocide in Modern Guatemalan Art

“As much as my work is about art, it’s truly about social change and how both disciplines are more powerful when joined together,” says Nikolai Humphrey-Blanco.

For his Division III project, “Genocide and Violence in Guatemalan Contemporary Art,” Humphrey-Blanco analyzed the ways in which art provides an alternative narrative to the violence perpetuated by the Guatemalan government during the nation’s 36-year civil war, which ended in 1996, as well as how art addresses ongoing issues of violence and injustice.

“I had been noticing that the civil war and the massive human-rights violations that occurred there for almost forty years were not often talked about in the United States,” he says. “I wanted to use this Div III as an opportunity to change that.”

His father is from Guatemala, so Humphrey-Blanco’s connection to the country, combined with his interest in politics and art history, he says, “quickly fueled the emotional motivation.”

Studying ten artists in depth, he broke up the thesis into three themes: racism as the motivating force of the genocide; voice and visibility in the counter-narratives of art; and how artists use literal and symbolic traces of violence and transform them into art and sites of discourse.

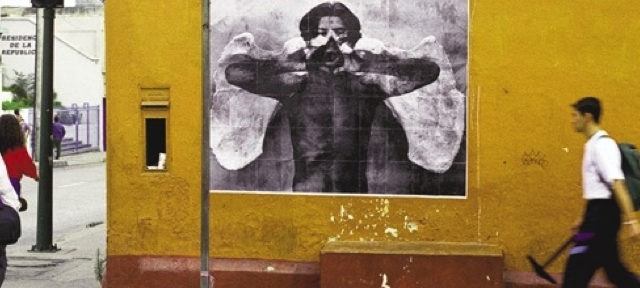

One of those artists is the photographer Daniel Hernández-Salazar. His most famous piece, Para que todos lo sepan (So That All Shall Know) / Street Angel features a photograph of the scapula bones (shoulder blades) of exhumed genocide victims overlaid as the wings of an “angel” shouting the truth of the genocide. “By plastering this image throughout cities, he was creating a critical counter-propaganda,” Humphrey-Blanco says. “He was shedding light on the violence perpetrated by the government and reclaiming the agency that had been denied from Guatemalans for so many years.”

The other artists Humphrey-Blanco studied are Regina José Galindo, Marilyn Boror, Jessica Lagunas, Jorge Linares, Maria Adela Diaz, Yasmin Hage and Alejandro Flores Aguilar, Estuardo Mendoza, and Jorge de León.

Humphrey-Blanco says he’s grateful for his Div III faculty committee: Lorne Falk, professor of contemporary art; and Associate Professor of Philosophy Monique Roelofs. “They provided the push I was looking for,” he says, “to dive as far into this work as I could.”

The Division III process, he says, presented opportunities to enhance his experience and also to challenge him. For example, he says, “I wasn’t fluent in Spanish before this project, but quickly had to become comfortable enough with the language to read detailed history accounts and interview artists about abstract theoretical concepts in their work. This project also challenged me to take a more active approach in research, contacting artists personally, making the first written analyses of many of these works and often not having any secondary sources available to help the process — it’s intimidating and not included in the typical set of research skills students are taught.”

Humphrey-Blanco says he plans to increase the exposure of these artists in the US by adapting his work for publication in an academic journal and helping to get the art into museums and galleries. Many of the artists he studied were excited about the interest expressed in their work, and said they hope to feature Humphrey-Blanco’s Div III in their archives.

“What I see most in this art is hope,” Humphrey-Blanco says. “The inspiring art that came out of this violence has changed Guatemala for the better, helping to move the country forward after too many years of trauma.”