Labor’s Love’s Found

Americans who view immigrants with suspicion and fear; corporations that exploit workers; appointed and elected government officials who represent Wall Street. Welcome to the United States in the late 1800s — an era with echoes of our own.

“I’m interested in how history is used to address what’s happening in the world now,” says Nichole Greene.

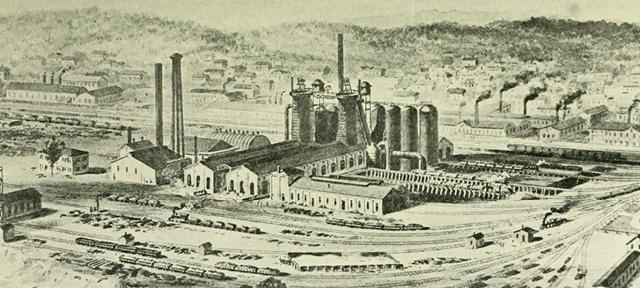

In her Div III project, Greene looks at the booming economy of Pittsburgh during the Progressive Era, which lasted from the late 19th century to the early 20th. The city’s massive expansion brought both immigrant workers and labor unrest, such as the infamous Homestead strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers in 1892

The bloody protest, which the Carnegie Steel Company broke with violent opposition, made national news and damaged Pittsburgh’s reputation. The city needed what Greene humorously calls “a rebranding.” Andrew Carnegie and other local leaders poured millions into revitalization efforts, among them major capital projects such as the Carnegie Museum.

Greene — a native of Carnegie, Pennsylvania, and third-generation Pittsburgher — analyzes the means of achieving the “new” Pittsburgh. There were new civic organizations, parades featuring immigrant workers performing the dances of their native countries, and the creation of public art, including a monumental series of murals, called The Crowning of Labor, in the Carnegie Museum. Painted by the American artist John Alexander White between 1905 and 1908 in New York City, the murals were transferred to Pittsburgh panel by panel.

“The murals have many allegorical scenes with male workers [often with bare torsos] receiving the rewards of labor from allegorical figures representing commerce, art, and science,” Greene says. “They reflect Carnegie’s ideas about self-improvement through education.”

In one panel, Carnegie is depicted in the guise of a medieval knight, rising heavenward as he is crowned by a winged female figure.

By portraying laborers in a noble light, it was thought, Crowning and other public artworks would weave together the disparate social threads of Pittsburgh, says Greene, “by getting the middle class to accept the working class” and see its members as a benefit to the city rather than a detriment.

For as long as she can remember, Greene has wanted to work in museums and historic sites. She transferred to Hampshire from Chatham College, in Pittsburgh, where she had majored in art history and museum studies. At Hampshire, she branched out into public history and other courses that rounded out her interests with an interdisciplinary curriculum.

Greene recalls an “aha moment” during a world heritage class taught by Assistant Professor of African Studies Rachel Ama Asaa Engmann (who is on sabbatical this year).

“We learned about uses of art and history for nation building and the creation of national identify,” says Greene. “I sat in class one day and realized that this was what I wanted to study.”

To research her Div III, she visited the archives at the Carnegie Museum as well as the main branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh over winter break.

“Nichole’s interest in relationships between labor and art is nuanced in this thesis and has provided her the underpinnings to pursue a career in a number of fields, such as history, art history, and city planning,” says Greene’s Div chair, Sura Levine, dean of the School of Humanities, Arts, and Cultural Studies and professor of art history.

“I used to walk through Pittsburgh as a child and I’d see a lot of monuments,” says Greene, “but I didn’t really understand what they were. Now when I look, I understand.”