Professor Lise Shapiro Sanders 90F Awarded NEH Fellowship for Book on Women and Romantic Fiction in the Early 20th Century

Professor of English Literature and Cultural Studies Lise Shapiro Sanders 90F has been awarded a six-month, $30,000 fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), which will support the completion of her book project, Working Women and the Modern Romance in Britain, 1900–1939: Reading for Pleasure.

Hampshire College professor and alum Lise Shapiro Sanders 90F has spent her career exploring the intersections of literature, film, and cultural history. Now, with an NEH Fellowship, she will take a leave of absence in fall 2025 to complete her latest book.

Her research examines how romance fiction, silent cinema, and women’s periodicals shaped the lives of working women in Britain. By examining the media that young women consumed, Sanders’s work sheds light on the evolving role of romance as both a source of pleasure and a reflection of social change. Working Women and the Modern Romance in Britain, 1900–1939: Reading for Pleasure will be published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2026 and will be available in independent bookstores and romance-centered bookshops alike.

We talked with Sanders about her forthcoming book, her approach to the topic, and what she hopes readers will take away from her work.

How does this book build on your previous research?

Reading for Pleasure developed directly out of the research for my first monograph, Consuming Fantasies: Labor, Leisure, and the London Shopgirl, 1880–1920 (published by The Ohio State University Press in 2006). I became interested in exploring what working women consumed in the interwar period (between the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II) — especially their reading matter and filmgoing habits. Young women have long been viewed as the paradigmatic consumers of romance fiction, and Reading for Pleasure asserts that the popular romance, more than any other genre, offered new possibilities for young working women as social actors and media consumers in early 20th-century Britain.

Has your experience as both a student and a professor at Hampshire shaped how you approached this project?

Interdisciplinary analysis is a hallmark of my graduate training in both literature and film studies, and my approach to teaching and research was shaped by my experience as a transfer student at Hampshire in the early 1990s. I wrote a Division III thesis project on literary texts and films inspired by the biblical figure of Salomé, and I learned so much about how to work across disciplines and incorporate theoretical and historical perspectives into my analysis.

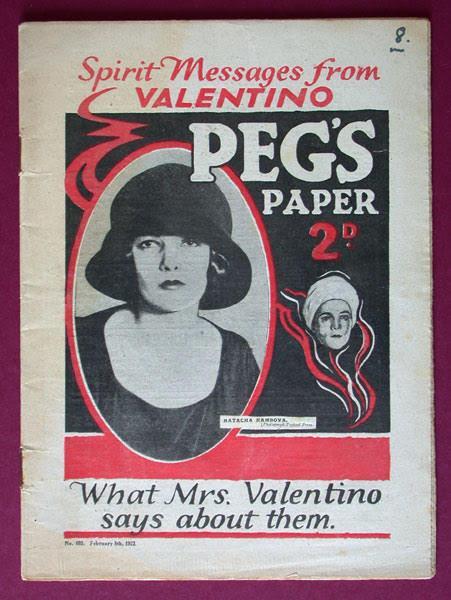

Returning to Hampshire as a professor in 1999, I began teaching courses inspired by my research into women’s literature, gender studies, and history. One of the first classes I taught at Hampshire was called Reading the Romance (inspired by Janice Radway’s book of that name), so I’ve been interested in studying popular culture and the romance for quite some time. I’m currently teaching an archival research course that I first developed with Associate Professor of U.S. Literatures and Cultural Studies Michele Hardesty in 2017, in which I initially presented the research for my first chapter on romance weeklies, the weekly two-penny magazines that published romance fiction such as Girls’ World and Peg’s Paper.

What inspired you about this particular topic?

I was inspired by my research in British archives, including the British Film Institute, the British Library, and the Women’s Library in London, which house many of the popular texts that I’ve been studying for the past two decades. Magazines such as Girls’ Favourite and Picture Show offer great insight into women as readers of romance fiction and fans of early cinema, and films like Beyond the Rocks (1922) — which was adapted from a book by the romance novelist Elinor Glyn and starred Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino — can help us understand the ways in which the popular romance crossed media forms. It’s an early example of what’s now called “intermediality.” Also, as I hope the students who have worked with me in courses on silent cinema will attest, these films are fascinating cultural documents, and also very absorbing and pleasurable to watch.

What do you hope readers — scholars, students, or a broader audience — will take away from your book?

I hope that romance will no longer be characterized as a “guilty pleasure” or as an aspect of media consumption that readers cannot admit to or be proud of. I’m happy to say I read tons of diverse, compelling, and well-written historical and contemporary romance novels. I’ve also discovered that the relationship between romance fiction and film/media is far more integrally connected than we might have otherwise thought, as evidenced by the use of “rom-com” to describe both film and fiction and by phenomena such as the streaming series Bridgerton. We can trace this connection to the early twentieth century.

Using an interdisciplinary cultural studies approach, Reading for Pleasure centers on the modern popular romance, read against the burgeoning star discourses and fan cultures of silent cinema. Romance fiction and film — alongside beauty columns, fashion illustrations, and editorial commentary in the periodical press — purveyed a culture of glamour, fashionability, and pleasure, yet a closer look at these texts, and the responsive engagement of the women who were their primary audience, reveals a simultaneous embrace and critique of the romance plot. An in-depth study of this genre can reveal how it resonated with the lives and experiences of working women in early twentieth-century Britain.

As we commemorate the centennials of women’s suffrage in Britain (1918/1928) and as women’s reproductive rights and freedoms are increasingly imperiled across national and global contexts in the present, it’s vital to reconsider an era in which young women’s voting power and social roles were in question. As we reflect on the role of popular culture and media in young women’s political engagement today, the lessons of a century ago are all the more relevant. In the coda to this study, I argue that contemporary scholarship on the consumption of romance fiction and film can provide compelling insights into women’s social and political agency in the present moment and opportunities to reflect on companionate partnerships, work–life balance, labor and consumer practices, and the role of gender in modern society.

Image 1: Beyond the Rocks (1922), Paramount Pictures

Image 2: Peg’s Paper (1927), Courtesy of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter