Student’s Investigation of Family’s Holocaust History Earns a Scholarship and Fuels Further Research

Recent graduate Sebastian Albert-Aranovich 18F provides a glimpse into his years-long historical investigation to uncover the journey of his family during the Holocaust.

Albert-Aranovich’s research earned him the esteemed Ikeda Soka scholarship, established by alum Elisabeth Carter 82F to support students whose academic work relates to topics such as peace-building, the science of mind–body health, and developing greater humanity in self and society. It also led to a deep look at Holocaust history, culminating in a multilayered Div III project about the Jewish Councils of France and the Netherlands.

What attracted you to Hampshire?

The College’s academic freedom and the promise of close collaboration with professors. I attended a small, progressive high school in Los Angeles where every student received narrative evaluations instead of traditional grades. Having been steeped in that environment, I felt that attending Hampshire was the best step for me to take.

What did you plan to study, and did that change?

Funnily enough, I first intended to study mechanical engineering. For my senior project in high school, with the help of my mentor, I built a fully functioning steam engine from scratch. With this experience, combined with a couple of years of experience working on motorcycles, I thought I would translate my love for machines into an academic curriculum. That didn’t materialize.

At the end of my first semester at Hampshire, I met with an academic advisor who wanted me to diversify my first-year studies. I told her I was interested in taking a class at Smith College that covered the history of the Holocaust. I indicated that I was nervous about taking a class in the consortium, but, sensing my excitement about the material, the advisor encouraged me to sign up. I did, and in the following semester, I quickly developed an intense fascination with the course, leading me to abandon the study of mechanical engineering.

You received the Ikeda Soka scholarship for your research project. Tell us about that work.

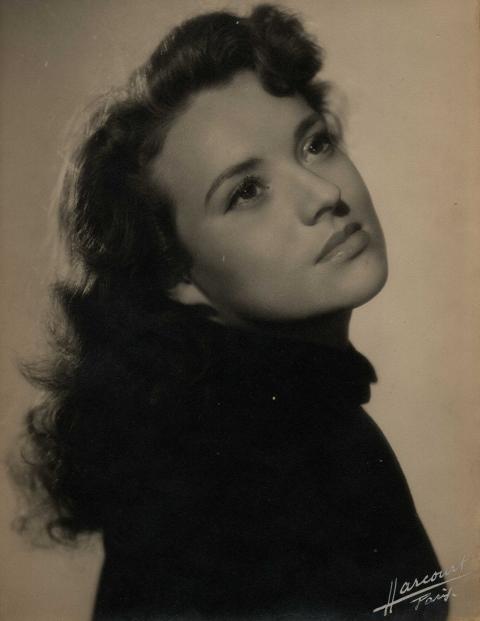

What earned me the scholarship was an independent project that I began working on in my first year at Hampshire. It was an intensive search for what exactly happened to my great-grandfather during the Holocaust. The only information from my family was that he was arrested in Paris, taken to a concentration camp just outside of the French capital, and ultimately murdered at the Auschwitz death camp.

I found a book at the Amherst College library, a massive compilation of every transport that deported Jews from France to the Nazi death camps. I found my great-grandfather’s name in the book and how he was deported: on transport 76, dated June 30, 1944. In the book, his date and place of birth are presented, as well as the day of his murder.

The next year, in 2020, hundreds of thousands of Holocaust-related documents were published online by the Arolsen Archives, the International Center on Nazi Persecution. I immediately hopped onto the online archive, and sifted through thousands of documents to find my great-grandfather. After much searching, I finally found something that mentioned him: a different list of Jews on transport 76. On this list, his residence in France was provided. Surprisingly, his address was not in Paris, but in Nice, all the way on the southern coast of France! I just didn’t believe my family story could have been incorrect, so I did more digging.

Just days after discovering what I thought was an error in the Nazi documents, I was reading a memoir by a woman who survived the Holocaust in France, and she mentioned the address of the headquarters of a Jewish organization that exclusively served Jewish refugees in Nice — it was exactly across the street from the supposed address of my great-grandfather, my great-grandmother, and my grandmother. This new discovery fit my family’s narrative, as my grandma and her parents were Jewish refugees who escaped the Soviet Union just after the Bolshevik Revolution. It was no coincidence that my family — Jewish refugees — were documented to have lived across the street from an aid organization exclusively for Jewish refugees.

With more searching, I found the hotel-turned-prison where my great-grandfather was imprisoned in Nice, the first concentration camp he was interned at, the second concentration camp, and finally Auschwitz, from which he never returned. After years of research, I rewrote my family’s story, uncovering tragic yet fascinating details that sparked in me an unbreakable, quasi-spiritual bond with my grandmother and her parents, despite their passing long before I was born.

Describe your Div III project.

From my independent research, I created a Division III that, among other things, investigated the umbrella organization to which the Jewish-refugee organization was conglomerated.

Ultimately, I examined two of France’s Jewish umbrella organizations with those of the Netherlands to see the impact of Jewish survival rates between the two countries. The title of it is “Degrees of Cooperation: The Jewish Councils of France and the Netherlands during the Holocaust.” My committee chair was Associate Professor of History James Wald and also on my committee was Professor of Comparative Literature Jeffrey Wallen.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently working toward fulfilling prerequisites to apply to graduate school. Though I’m looking at different programs, I have my eye on a master’s in public policy.